Breaking Open the Mainstream

A conversation with Rachel Zemach, author of The Butterfly Cage

Hi everyone,

Hope you’re all taking care, wherever you are.

It’s a difficult moment for disability advocacy in this country, among so many other issues. Later tonight, I’m planning to tune into the new PBS American Experience documentary about the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. It’s called Change, Not Charity, and it’s directed by Jim LeBrecht (of Crip Camp fame). Check out the trailer below:

Go watch this film tonight, too, if you’re interested, or catch it streaming online sometime soon. The timing really couldn’t be more important.

As I try to keep up with the larger news cycle, and also try to keep thinking through what my own advocacy work looks like nowadays (key word being try), it all feels like another reason to continue pursuing sharp and thoughtful conversations with each other.

And with that, I’m very pleased to present another installation in the Q&A series — this time with Rachel Zemach, a former teacher of the Deaf who is also the author of The Butterfly Cage, a memoir about her ten years of teaching in a public school in California.

(A note for readers: you’ll note my occasional back-and-forth about the lower-case versus capitalized Deaf. Since I always try to follow other people’s preferences, today you’ll see the upper-case version!)

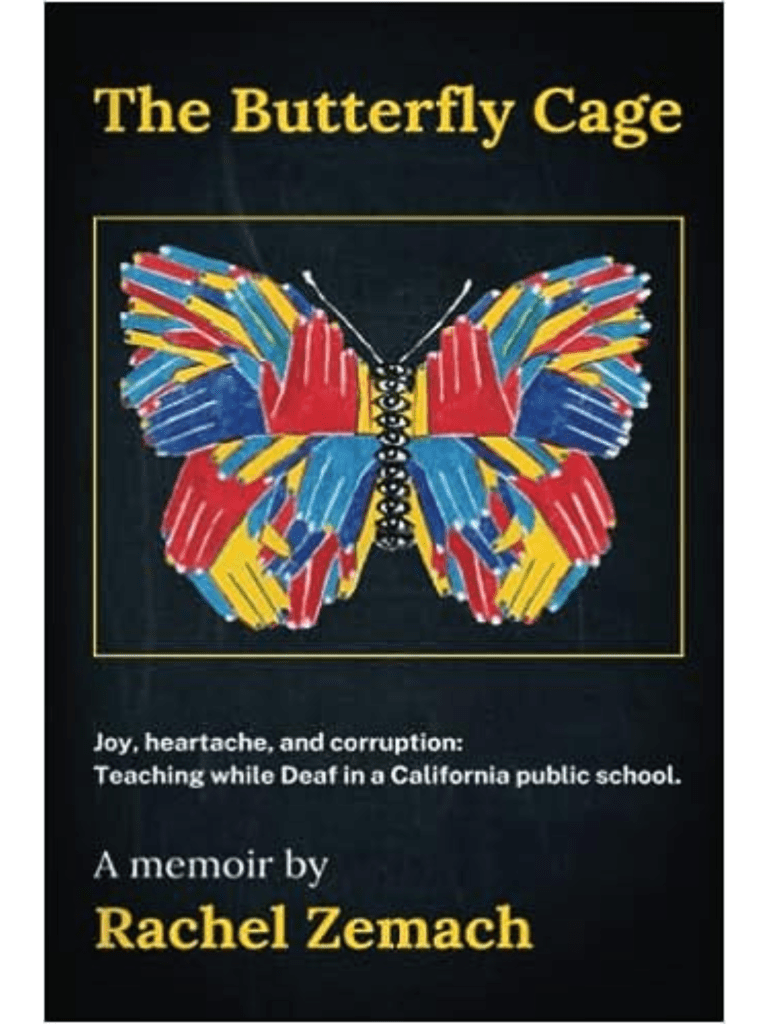

As often happens in my life, I first became aware of this fellow Rachel’s work through the Internet. When I first saw mention of The Butterfly Cage after its publication in 2023, I felt intrigued: by its title, as well as by its cover, which features artwork by the wonderful and inimitable Deaf artist Nancy Rourke. Rachel and I connected through online channels, then followed each other for a little while before we got the chance to chat more directly. I soon realized that, while I’ve read a few other books about various DHH people’s experiences in mainstreamed education, I had never seen one written from the perspective of a Deaf teacher.

I was a mainstreamed kid myself, and in many ways my own forthcoming book is a memoir of the mainstream, of growing up during the years right after the ADA. I’ll stand right up and say the mainstream is always complex. It involves many decisions on the part of each individual kid, family, and classroom. The quality of mainstream programs varies widely. And Deaf kids who grow up in mainstream schools have so many more complications to navigate than their typically hearing peers do, from the linguistic to the social and emotional and cultural. This is true even when these students gain access to consistent and high-quality accommodations for their educations, like I did via ASL interpreting and other accessibility measures such as in-class notetaking.

All of this is why I believe it’s important to have more open discussions about our schooling, as well as families’ at-home expectations for communication. What is “inclusion,” anyway? What are the different shapes it can take in school, and what are the barriers that can arise for DHH kids, from language deprivation to social exclusion? How do teachers promote DHH kids’ flourishing, both in the mainstream and in Deaf schools?

These are the kinds of questions that Rachel Zemach has thought about for a long time. They’re the complications she explores in her book. Her heart for her students radiates throughout The Butterfly Cage, and I’ve felt her deep zest for teaching and interpersonal conversation through the discussions we’ve had online, both via written words and via video chatting in ASL. Since connecting over our shared writerly interests, we’ve discovered several folks we know in common (of course). We’ve discussed many of the nuances of Deaf education, as well as of crafting a life in both ASL and English. I’m always so grateful for this dynamic and interconnected Deaf world, for all the people working and starting conversations within it.

Go check out Rachel’s website here to learn more about her writing, and also check out The Butterfly Cage here.

Especially with our ongoing political uncertainty in the U.S., as well as mounting threats against disability-inclusive education, today’s conversation feels very timely to me. As complex as mainstreaming already is, there’s so much we still need to protect to give DHH and disabled kids their best chance at succeeding in the general-education system. Right now, several states are raising a lawsuit against Section 504 protections for students with disabilities. The attempted dismantling of the U.S. Department of Education could have enormous consequences for the resources made available to these students. Last week the Department of Justice removed several guidelines for businesses seeking to comply with the ADA. And the list goes on.

If you would also like to keep up with this sort of news, I suggest checking out the Disability Rights Watch account as one place to start. (And big shout-out to fellow writer and advocate Sara Nović, among others, for working so tirelessly to gather and circulate news and actionable resources.)

Now, without further ado, turning it over to the other Rachel!

This book reflects on your years of experience with teaching Deaf students in the public school system. Was there a specific moment when you knew you had to write this?

It was more like an accumulation of events and moments, starting on my very first day there! Over my ten years on the job, there were many moments where I felt so gob-smacked, enraged or saddened by what had just happened that, in the last three years there, I started getting strength from the idea that some day I must, and would, write about it all.

One such moment was when we had a wonderful, famous Deaf guest speaker come do a workshop called “Deaf Education from a Deaf Perspective.” The next day I found that, rather than absorb her messages — and considerable expertise — the general education teachers had roundly decided to reject all her suggestions. Another was when I found the administration was planning to combine the two Deaf classes; in one room, one teacher; grades K-6 would be taught together. It was those moments — where I felt hopeless to make any change within the system — that I felt I should at least try to take action via a book.

It seemed there was zero accountability and zero oversight, and that parents and the public had no idea what was going on there. And I knew the things I encountered were not uncommon but rather attitudinal, so I wasn't just writing about one school, but how the thinking of hearing staff and administrators impacted Deaf/hard of hearing children in US public schools.

My experience wasn’t all negative; I absolutely loved teaching and there was a lot of laughter in my classroom. And almost daily something would happen in the classroom that was so funny or so interesting that I thought, “Wow, it would be so cool to share this moment with other people.”

What are some of the biggest challenges you saw during your time working in mainstreamed education?

The biggest challenge was the sheer level of ignorance. Not due to malice or any bad intentions, and not anyone’s fault, but still often quite shocking. It started in the first interview, where my ASL skills were not questioned at all, despite fluency and language modeling being essential skills for a good teacher of the Deaf. And it continued to show up almost daily in the policies, attitudes, and incidents on campus.

Being Deaf was seen by administration through a deficit-minded, disability framing rather than a linguistic, cultural minority one. There was also no sense of respect for the expertise of Deaf professionals, or even Deaf organizations. So even though they were basically well-intentioned, there was a certain arrogance to their behavior that undermined their ability to do well for DHH children.

In my first year teaching, I encountered a psychologist who “counseled” profoundly Deaf students, without knowing ANY ASL… meaning she had no more meaningful communication with the student than one would have with a goldfish. Yet she insisted she didn’t need an interpreter and wrote psych reports that were then used in IEP meetings! There also were no substitute teachers who signed, which meant that when a sub was there, the classroom aides would be in charge of teaching, while the substitute teacher could do no more than pat the kids on the head. The job was really bizarre at times.

After a few months teaching I realized I was witnessing extreme language deprivation. The students were all smart, attentive, and hungry to learn. But they could not answer even simple questions like if they had a pet, or siblings, or what they did for their birthday. They would just smile and nod and sign, “Yes! I like that! Like, like, like!”

I soon realized they had not been exposed to ASL, either at home or at school. Their parents did not sign beyond a few simple homemade gestures (for things like sleep, no, bad, eat), thus their brains had not developed in the normal way, via having a foundational language with which to communicate, and with which to think.

So I had a class full of five-to-ten-year-olds whose language levels were extraordinarily delayed, yet the administration, not understanding this (nor being teachable when I tried to explain it), expected me to be able to teach them reading, writing, math on a par with their peers, sans language. I WAS able to, and taught ASL simultaneously, using absolutely everything as grist for the mill of language development, and loving every minute of it, but it was fantastically hard to do. And at times I would hit odd roadblocks, since they had missed the first 5-7 years of language acquisition. Their abstract thinking was extremely weak, and so was their critical thinking and their sense of time.

The administration also did not understand the concept of (or benefits of) children having a positive Deaf identity, or the existence of Deaf culture. To them, assimilating into the “hearing world” was the priority and goal — yet, in my observation, that approach often meant sacrificing their education. The student would be in mainstream class, going downhill in many ways, yet it would be celebrated as a win by staff.

And a follow up: what do you wish more teachers in the public school system knew about working with DHH students?

I wish the language deprivation issues that are so common, and the visual learning styles of Deaf kids and the beauty of the culture, were things administrators and staff understood. And likewise, the ways in which regular curriculum often does not work with our students.

I have a fantasy of ALL students, whether hearing, hard of hearing or Deaf, learning ASL across all grade levels. Kids learn ASL remarkably fast and intuitively, so it is not an impossible goal at all. And so often the exact students who struggle with academics are the ones who pick ASL up BEST, since it involves another part of the brain, one’s visual-spatial skills, so it’s a self-esteem boost for them that also opens doors career-wise.

It could be done by Deaf people making educational ASL videos, and a curriculum that is fun and game-based for the lower elementary ages, while vocabulary building, conversation, field trips, history, and diversity could all be integrated in middle school through high school. By high school most students would have a working knowledge of ASL. The benefits to hearing people would be many and profound, while the biggest challenges of Deaf people in society would simply vanish as a result, since they tend to be communication-based.

Staff, from bus drivers to administration, could also be taught a basic vocabulary of 100-200 signs each, eliminating the extremely awkward and problematic communication gaps between themselves and the Deaf students on campus.

Parents of Deaf students should be urged and provided with resources to learn ASL. The vital importance of deep, easy communication between parent and child (and siblings) should be consistently emphasized to all parents, all the time, by all staff, and reinforced with policies — for example, you can’t enroll your child without a commitment to learn at least 200 signs — and free resources.

Mainstreaming a child in a hearing class or school can go well; it can even be fantastic. But it must be done extremely carefully. To simply throw Deaf students in a hearing environment and call that a success is naive and can have lifelong impacts.

Don’t get me wrong, though. The joys of Deaf education and Deaf/hard of hearing students are as voluminous as the problems in the public school educational system can be. Watching a human mind expand exponentially when exposed to a language is both exciting and an honor. In my classroom, ASL acted like a key activating the inner workings of the student’s brains, and it was quite fascinating.

In your book, you also discuss your own growth into a stronger sense of Deaf identity. Could you describe what that was like for you?

When I started teaching, I called myself hard of hearing or deaf, with a lowercase d. I felt I did not truly belong in culturally-proud Deaf spaces, even though I was too deaf physically to access hearing spaces well, either. I knew a lot, theoretically, and had been told a lot by Deaf friends, about audism and typical Deaf experiences. But as a late-deafened person (from age ten) and one born into a very literary family, my own life had been quite different. So I understood certain things about Deaf oppression or typical challenges only abstractly.

As the years went by, though, teaching Deaf kids in a hearing school delivered a whopping education to ME. I saw firsthand those things I had formerly only read about or been told about, like a Deaf student asking if he would become hearing — or die — at age 18, since he’d hardly ever met any Deaf men. I saw both the incredible power of ASL and the denigration of it by school staff and medical specialists. I saw what excited my students and what harmed them, and how easy it was to grow their language, and their inner strength via a sense of Deaf identity.

I also saw firsthand the discrimination that occurred, unintentionally, on campus, both to my students and myself. Bit by bit I began to feel radicalized, and more confident in my place in the Deaf world, due to gaining a deep understanding of it from my work.

I changed a LOT during those ten years teaching in the mainstream. It was not an easy education — it was brutal very often, in fact — but I was thrilled to feel unambiguous about my identity. I just wished I’d reached that point earlier. One example of why is that, feeling hard of hearing, I thought my two daughters were COHOHAs (child of a hard of hearing adult) rather than CODAs (child of a Deaf adult). Looking back, I am sad they missed out on their potentially enriching CODA identities because of where I was in my journey at the time I raised them.

I began to see that I was Deaf, and proudly so, ironically in that very hearing environment. My love for the students, and for teaching, was no small part of that.

What are some ways you’ve continued to learn and seek creativity in your personal life, now that you’ve retired from teaching?

I’m doing some tutoring online, of both Deaf students and ASL to adults in their lives. It is great to be teaching again, and one-on-one is amazing, because without the classroom management issues, or the need to differentiate instruction to meet many levels and ages at once, one can teach so much faster! I’d like to collaborate with a Deaf literacy program to share knowledge in an area I am passionate about, teaching reading comprehension and writing skills to Deaf students, especially with the great technology available to us all now.

I’m trying to market my book, although marketing a book is a very different animal than writing one! I’ve been writing a lot of articles too, and they are fun because they are SO much easier than writing a book, but also can say a lot and reach a mainstream audience. I am also doing a revision of my book and trying to get it translated to Spanish, make it into an audio recording, and am beginning to explore book number two, which will be about “in-betweeners.”

Let’s put it this way: I don’t feel very “retired,” nor do I want to be. I love working. And I love keeping in touch with and seeing my students’ progress in life.

How has the process of writing the book been for you? What advice would you give those considering doing it?

Oh my goodness, I have learned SO much in the process, and also gained so much from it. Not financially, but in terms of new friendships, a new understanding of what a book actually is, and how much goes into each one. I don't remember who said it, but some famous writer said that writing is simply moving words around on a page, all day long. Not glamorous at all. But the experience of massaging a particular aspect or moment in one’s life repeatedly until you have shaped and polished it to perfection, decided what is vital to share and what isn’t, is extraordinarily powerful.

The trauma one has experienced and is writing about is diminished through the sheer act of writing it. It’s as if, having put a tough time in your life to good use, you have taken your power back, and it no longer has much hold over you. Then, too, sharing it with other people, having strangers contact you out of the blue saying your book made them laugh and cry and changed how they think (and sometimes how they approach their Deaf education jobs) or that they feel SEEN, is also amazing. Seeing, via readers’ comments, that they truly understand it, understand what you lived through, and what you tried to tell them via the book, is wild. One administrator told me she shifted the focus of her large DHH program from “Total Communication” to “bicultural-bilingual” after reading it. Many parents have newly signed up for ASL classes, and one woman shared the book with her sister and felt her sister finally understood her Deaf sibling’s life experience after reading it.

Writing a memoir is like opening a door to your heart and inviting the general public in, but in a measured and careful way, where you take the best and most memorable, funniest, most important things your life has taught you and offer them to your readers through scenes and stories. It is a chance to say things, rather than just passively live through experiences and cope with them.

I think if you have a book sitting inside you, nagging you over years to get it done, there is a reason for it, and the payoff will be tremendous, even if it's only internal! The journey of writing it, and its trajectory in the world, is not something you can predict. It will become its own thing, one you have not yet met. Publishing is a long and complex process, and competitive, but I truly feel if I could do it, so can you. And even if one is writing about a hard topic, it can be a happy, stimulating, and exceptional experience turning it into a book.

Big thanks to Rachel for sharing these insights with all of us today. (I say “amen” to these closing thoughts about book-writing!)

Now go out and keep reading, y’all. And keep writing, advocating, creating, conversing, questioning, inciting, revising, learning, engaging, and dreaming. Leave any comments below about what’s sustaining your own educational work these days.

Laughed at the line about "conversing with a goldfish". How true.

Thank you for this opportunity to read about my friend Rachel’s thoughts and reasons behind writing her book. Indeed, many of these facts she shares reverberate with me as I think back to the years I also spent as a Deaf person teaching DHH kids in the mainstream. It reminds me of the year after I taught ELA at a Deaf school and had similar students in a mainstream high school. The attitudes of the administrators, supervisors and even the hearing teachers of the Deaf was atrocious and dictatorial when they saw my differential instruction based on what I saw that worked at the Deaf school.

I also align with the benefits of writing about our experiences as Deaf people. I have done that with my two novels in the soon to be released Resilient Silence Series. Some of the characters in my novels are modeled after the oppressive teachers, service providers and parents with whom I interacted as a TOD. So you are right, there is a healing and redemptive quality of getting the message out there and publishing our work as Deaf creatives in literacy.